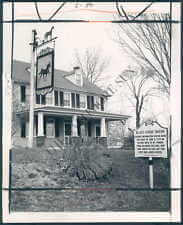

The Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge over the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, in the vicinity of Wright’s Ferry. U.S. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, “Built in America” Collection. Public Domain.

If this post already sounds familiar, see my post on the 1811-13 watercolor by Secretary to the Russian Consul-General Pavel Petrovich Svinin (MMA 42.95.37) of crossing Wright’s Ferry, near Columbia, Pennsylvania.

While at Winterthur this summer for a research fellowship, I came across a travel journal by Samuel R. Fisher (Mic. 296.1 See the Finding Aid here. The original is in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania). The series of journals include trips to England, South Carolina, and a “Horseback Trip in ‘Back Parts’ of Pennsylvania, with John Townsend. Also – South to Winchester, Va. Journal 4 Month 12th, 1787 to 6 Month 3rd, 1787.” I was looking for descriptions of women’s dress in the back country communities he visited, but Fisher is most descriptive about the topography and Quaker meeting houses on his way through the piedmont and mountains. He travels by Fort Necessity, noting George Washington “had a battle with the French & Indians & near this place” and the Youghiogheny River.

Today, there are myriad ways to cross the Susquehanna whenever you wish. Wright’s Ferry was established early in the 18th century and operated until 1901. In 1787, Anderson’s Ferry opened and lessened traffic at Wright’s Ferry. In previous years, it could take several days for your turn to cross the ferry. Fisher, crossing in 1787, had only to wait for a few hours for the wait for the various canoes and flatboats that made up the crossing.

4 mo: 14 Rose early, sat out & reach Lancaster 18 ½ Miles by 9 O’Clk where breakfasted, calld on Charles Hamilton, Mathias Slough & Myers Solomon on some business, abt 11 O Clk sat out in Co. with Daniel McPherson, his Daughter & Son Isaac – reached Wright’s Ferry abt 1 OClk here dined. I calld to see John Townsend at the Widow Barber’s a friend close at hand, where had just been a Meeting & found him with J Scattergood & sundry other friends. D Mc Pherson Son & Daughter proceeded over the ferry. I waited for Jn Townsend parted with J R Elam who returnd to Lancaster & crossed Susquehanna in Co. with J Townsend , J Scattergood, P Yarnall T or J Speakman reached Yorktown 10 Miles about SunSet. J Townsend & J Scattergood lodged at Elisha Kirks, D Speakman & self at Peter Yarnall’s where were kindly entertained.

A Ferry Scene on the Susquehanna at Wright’s Ferry, near Havre de Grace. Pavel Petrovich Svinin (1787/88–1839), 1811-13. MMA 42.95.37.