You may have been to Old Sturbridge Village, Colonial Williamsburg, or Plimouth Plantation. Staff at these sites use authentic costuming in order to educate the public about the past. Clothing is the first thing visitors notice; they know when they see the bonnet, the skirts, etc. that they can ask you a question that will help orient them to the experience.

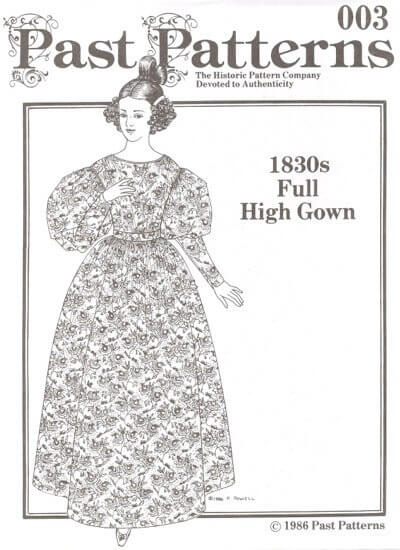

The first garment I ever made was an ugly green and pink skirt with an elasticized waistband. The second garment was this 1836 gown, using this pattern from Past Patterns.

My first museum experience was at the living history site Heritage Hill State Park in Green Bay, Wisconsin. We presented first person interpretation, which means that staff interpreters speak to you as a person living in 1836. In my role as fourteen-year-old Sarah Wilcox, I would profess not to know what airplanes and microwaves are. Sarah, who was an actual person, moved to Fort Howard in Green Bay to live with her uncle, a surgeon, after her parents died in the Detroit cholera epidemic in 1832. As an aside, I do not necessarily like first person interpretation – I feel that unless it’s a scheduled program, that it can confuse visitors, or leave them feeling alienated or unwelcome. I much prefer to talk about what they are experiencing, using my historic clothing as a prop.

Needless to say, period clothing looks strange to those visitors with only a vague notion about history and looking for something fun to do on the weekend with their children. It prompts them to ask questions not necessarily appropriate in public. “How do you go to the bathroom in that?” “What do you have under there [skirts]?” “How do you take care of, you know [insert hand gesture referring to menstruation].”

They touch you. In the 1830s, women held out the large leg o’ mutton sleeves with ruffled or down-filled sleeve puffs worn underneath their gowns. Seeing as not all of the staff had sleeve puffs, sometimes we resorted to newspaper for special events, such as the wedding we recreated. Of course, a visitor walked right up and started to squeeze my sleeves. “What do you have in there?” At another site, I even had an elderly woman pulling up my hoop skirt, wanting to see what was underneath. She didn’t stop to ask. I became a full-life fashion doll, turn me over and see what’s underneath. I enjoy discussing what I’m wearing – it makes a good segue into discussions about the textile industry and women’s history.

But good manners are always in order.