Collage of engraved portraits on exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in “A Will of their Own: Judith Sargent Murray and Women of Achievement in the Early Republic.”

I was killing time before my talk for the Washington Conservation Guild on February 7. The old Patent Office serves as the home to two Smithsonian Institution museums, the National Portrait Gallery, and the American Art Museum. The Patent Office building began construction in 1836 and its third floor interior is a mid-19th century exhibition hall to behold, in riotous color.

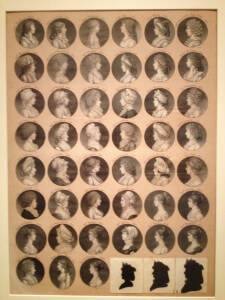

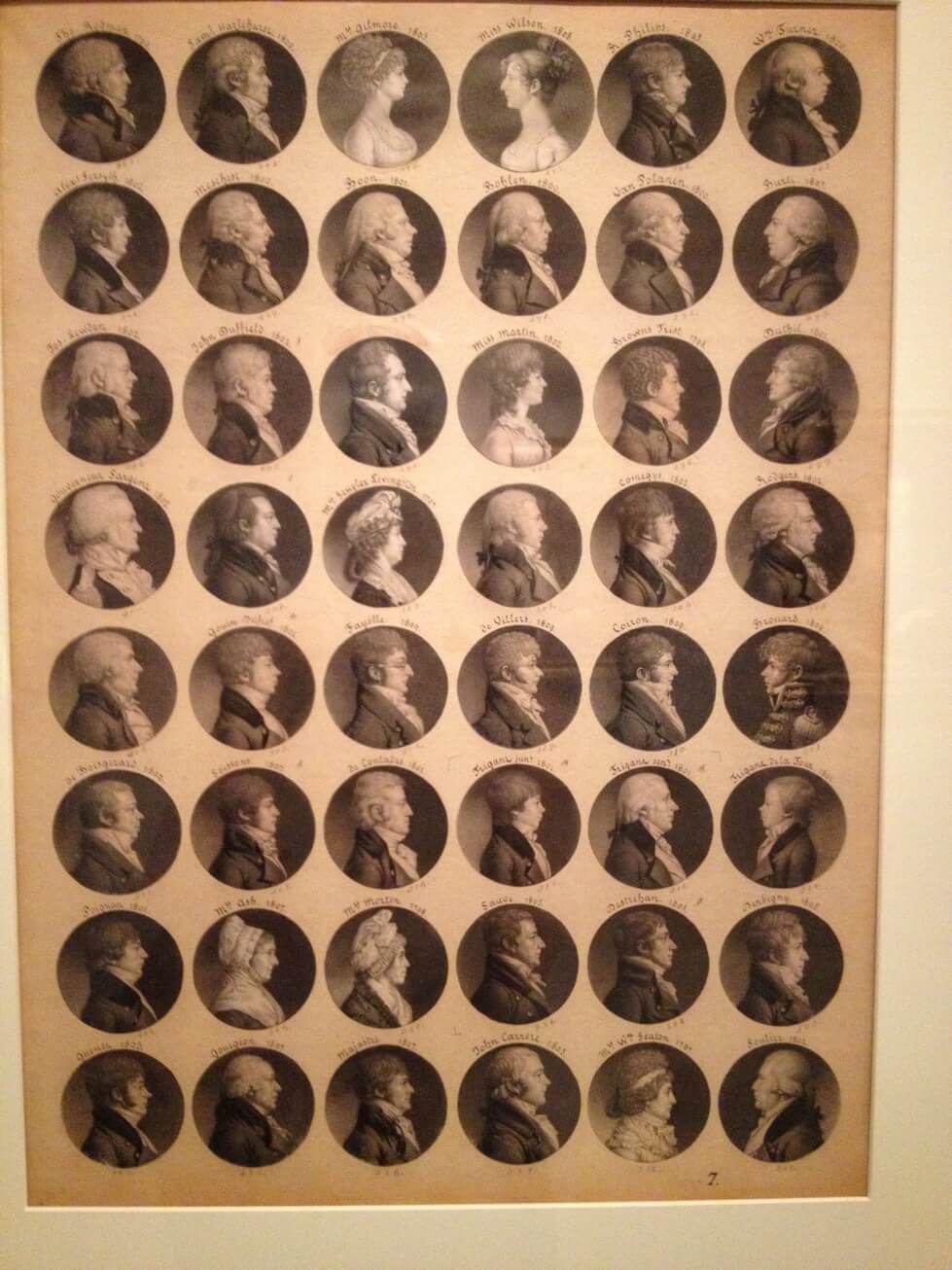

On the first floor, the National Portrait Gallery had a few exhibitions around various themes: Civil War portraits, African American portraits, Amelia Earhart, Civil War generals photographed by Matthew Brady, portraits of early prominent American (a bit boring). But in “A Will of their Own: Judith Sargent Murray and Women of Achievement in the Early Republic,” the curator highlighted Theodosia Burr Alston 1783–1813 using a small engraving among a page of mounted engravings (and a few silhouettes), cut, labeled with the name and date, and a cataloging number.

Unfortunately, the exhibition label only spoke of Theodosia, and not about the curious arrangement of collected visages of prominent persons. The credit line reveals nothing, reading “National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.” It’s likely these are 19th century assemblages, used to catalog the appearances of notable Americans. It is a window into past museum practice. Their peers include cataloged specimens at the National Museum of Natural History, insects numbered and stuck on a pin.

It’s a pity that the exhibition chat couldn’t have revealed more about these peculiar assemblages.

Testing