I fully expect Masterpiece Classic’s Downton Abbey to inspire the costume choices of many next Halloween (see my post on Downton Halloween costumes). Dr. V and I clung to the compelling story lines from above and below stairs every Sunday evening. We even rushed home from our Super Bowl party to stream that night’s episode online. For years, Halloween parties have often had a French maid character, but will people take cues from Anna the head housemaid, or Mr. Carson, the butler? More likely, Halloween celebrants will choose above stairs characters for their inspiration: the Dowager Countess, Lady Mary, and Lord Grantham.

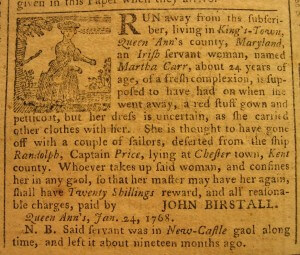

Advertisement for Martha Carr. Pennsylvania Chronicle, February 8, 1768. RL Fifield Photo, Library of Congress collection.

As part of my research on 18thcentury working class clothing, I have been studying an altogether different kind of servant: the indentured and enslaved female servants who immigrated to the American colonies. Many of our ancestors came to the colonies this way, either by choice or capture. They served as house servants, assistants in their master’s businesses, and agricultural laborers. Most women servant immigrants had no specialized occupation or training, compared to their male counterparts. For the servant who decided to run away from the household, their master would post a newspaper advertisement for their capture. To help in their identification, the master would list the clothes the servant might be wearing, whether they belonged to the servant, or if the servant had stolen them upon her departure.

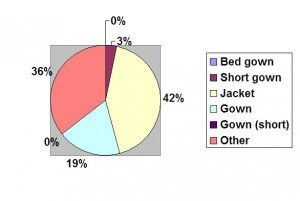

A chart showing the distribution of upper body garment data for enslaved women in Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, 1750–1790. The other category includes garments such as wrappers, sacks, and waistcoats. The 0% reflects that the term “bed gown” was not used for garments worn by this population. Chart: RL Fifield

I created a database that now houses records for 1000 women and their 6000 garments. Why? Anybody got a photograph from 1750? (for those not in the know, photography sprung from work done in the 1820s and 1830s). Poor and working women are the invisible population in history. Unless they did something exceptional, such as runaway or commit a crime, most immigrating women of the lesser sort are not documented at all; their history is lost. This is especially true of enslaved women. Runaway advertisements document not only clothing, but also physical characteristics, habits, skills, and other information. I started on this journey to study clothing, and to discover, if possible, elements of choice and fashion among women of the lesser sort. This data can teach textile and economic historians a lot about trade at the time, and can inform living history programs. To study these women as a group is to recover their community, rather than considering these women as spot mentions, individuals without context.

New: see the full article online here. If it doesn’t come up, go to the home page and search again.

Great blog Becky! Keep up the good work.

Thanks Barbi!! I’m enjoying it, and glad to be writing again.

[…] other posts on the Runaway Clothing Database project click here, here and […]

[…] predicted in this post from April that people would be hot to trot for Downton Abbey influenced costumes this Halloween. True to […]

[…] of indentured and enslaved women (see my article here, as well as previous posts on the project here, here, here, and here) makes this a fascinating resource. By locating where their masters lived, I […]

[…] as well as owners of women who I have cataloged in my Runaway Clothing Database (here’s an earlier post on that […]

[…] in residence at Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden working on my 18th century runaway project and participating in a preventive conservation exchange. I’m extremely grateful to have this […]

[…] how 18th century working women acquired textiles and garments (see an earlier post on the project here). Surprisingly, train fanatics haven’t documented this little station extensively online. It […]

[…] century working class through my study of 1000 18th century newspaper runaway advertisements. (see this post for more information about the project – check the servants category on my blog for further […]

[…] The servant in this image is a perfect analogy for what we’ve lost in our understanding of working dress of the 18th century: the details. Learn more about my study of working women’s dress through newspaper runaway advertisements here. […]

[…] living in North America, 1750-90, who were advertised for recapture in newspapers (read a previous post on the project). I used this information to create a database of 1,000 women and their 6,000 […]