Click here for Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

And then, my family members went on vacation. Like many families, they visited the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. But unlike your average Washington, D.C. tourist, the Coles stayed several months.

Thanks to Doug Owsley, Forensic Anthropologist and member of the Department of Anthropology, I learned more about my ancestors than documentary evidence could ever tell us.

Doug has been researching how we physically became American for decades. He can tell whether a 17th century skeleton belonged to a person who was born in Europe and died in Europe, or was born in the American Colonies and died in the American Colonies, or if that person was born in Europe and died in the American Colonies. Our bones’ composition changes depending on our diets. The events of our lives are recorded within our skeletons, which is the subject of Owsley’s excellent exhibition Written in Bone: Forensic Files of the 17th-Century Chesapeake (visit this link for a video and educational materials in relation to this exhibition). In the show, Doug and his team tell the story of 17th-Century people through the stresses and signs left on their skeletons at the end of their lives. The exhibition closes on January 6, 2013.

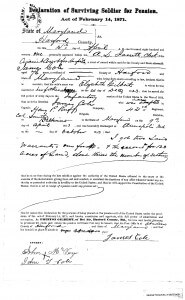

My 19th century farmer relatives provide a different set of data for his project. By studying the isotopes in the bones of my great great great great grandparents, he was able to indicate that James Cole ate more wheat products, than his wife Elizabeth Gilbert, who preferred corn. James had also suffered an injury to his rib-cage, after which his torso was tightly bound, causing the knitting ribs to grow downward. While he was a War of 1812 Veteran, nothing in his pension papers indicates that he was wounded during his service. But has a farmer, there were plenty of opportunities for serious injury.

We met with Doug Owsley and members of his team when we went to pick up the family remains in October of 2011. Doug spent two hours telling us about each person. Unfortunately, it was hard to know much of the other four people. The infant had no remains; only the rootmat that had grown where the infant had laid indicated its existence. The eleven-year-old was identified by a single tooth that remained. The six-year old girl left only enough to indicate her gender. The adult woman left only a partial skull.

Rather than lose their identities completely, it was important to me to gain as much information as we could before reburial. I felt in my mind it was a way to compensate for the relocation. They are now buried at Baker United Methodist Church’s cemetery outside Aberdeen, Maryland. James and Elizabeth’s children and grandchildren are buried nearby.

[…] here to read the final installment of Digging Up My Ancestors – including a trip to visit Doug […]

[…] here and here for the next […]