Cole Family Burial Mound, Aberdeen, MD, 2010. The mound was left after gravel stripping operations in the 1940s, and has now been replaced by an office building. The tire tracks had been created by ATVs.

Yes, literally. After the application of trowels, sticks, and small brushes, out of the ground came the fragments of people with whom I share DNA. It’s a long story, so I’ll offer snippets of the story over a few non-consecutive posts.

January 2010 began with a phone call from a very distant cousin, a Mr. S, who is a genealogist living in Harford County, Maryland.

“You should be receiving something from a lawyer.”

Who wants to receive something from a lawyer? The letter arrived: my great-great-great-great grandparents’ burial site had been found on one of the last undeveloped sites in Aberdeen, Maryland.

Two years later, the site is now home to an office building sandwiched between Target and a 1950s suburban development that includes the 1860s house of my great-great grandparents. It had been part of a family farm owned from 1757 to the 1940s, when it was sold for a gravel pit. Mr. S had been working with the genealogist hired to locate any descendants, and I was one. Fortunately for us, a Daughters of the American Revolution cemetery preservation project in the 1960s documented the tombstones at my GGGG grandparents’ burials. In the intervening fifty years, the tombstones disappeared.

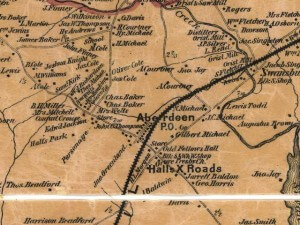

A Martenet Map from 1878 that shows several Cole family members living near the intersection of Bush Forest Chapel Road and Paradise Road in Aberdeen, MD.

Harford County sits at the top of the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, where the 464-mile-long Susquehanna River releases into the bay waters. Havre de Grace is the town that sits there today, renamed after the Marquis de Lafayette compared the town to Le Havre in France. Its claims to fame include its burning by the British during the War of 1812, tomato and shoepeg corn packing houses, duck hunting, W.C. Fields watching horse races at The Graw, and the Italian mob running liquor during Prohibition. Aberdeen, somewhat of a poorer cousin to the south, was a farming and packing house town. The creation of Aberdeen Proving Ground in 1918 led to the scrappy sort of boom you see in military towns and many residents, including my family, were employed by the base since its inception. My mother’s family has lived in the area for nearly 400 years.

The developer’s plan was to disinter the bodies using a local funeral home and move them to a graveyard in Darlington, Maryland. It was rather unfortunate for the developer that the direct descendant is a museum professional with an interest in family history. Land transactions involving dead people in the way can run emotionally hot. The developers have deadlines to meet, and I obviously wanted to get my family disinterred by archaeologists, rather than by shovel. Relocation of the remains included an unexpected trip to the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution which told us more than archival documents ever could. I’ll share the odyssey of reclaiming, identifying, and reburying my GGGG grandparents over a few posts. More to come.

If you want to read subsequent installments of this post, click here, here, and here.

[…] Click here for the first post on the Cole Cemetery relocation. […]

[…] here to read Part I and Part II. Charles Darwin and his son, […]

[…] here for Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3. Gibb Archaeological Consulting Crew, Cole Cemetery site, Aberdeen, MD, 2010. […]

[…] the Cole family, see my series Digging Up My Ancestors about their cemetery move, beginning here). But it was really a mess out there, and seeing as Dr. V and I were going to borrow my Mom’s […]