Oil painting on canvas, Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). Cherryburn, Northumberland, National Trust. NT 530359.

In digging through the British Museum online collection database this week for a project, I tripped over the wood engravings of Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). Operating mostly in Newcastle for his entire career, Bewick’s rural upbringing led to an interest in natural history. Bewick used metal engraving tools to carve end-grain boxwood blocks, resulting in wood cuts of exceptional durability and detail.[1] Interestingly, when having his bust made, Bewick insisted on being depicted not in a toga, but in his everyday dress and with smallpox scars depicted. Bewick’s tooled blocks were so intricate they challenged printers in their correct use, so rendering himself accurately was of great importance.

If this image had sound, it would be “weeee!” Book illustration from Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘Mother Goose’s Melody’ (London: 1781, p.37). Trustees of the British Museum. Accession Number 1882,0311.3817.The image that drew me into Bewick’s work was the realistic depiction of a woman swinging a child by the hands, suggesting squeals of laughter.

You can search the over 3,000 prints made by Bewick and family in the collection of the British Museum online. A 2013 publication, Thomas Bewick: Graphic Worlds by Nigel Tattersall, focuses on the work Bewick produced for hire, such as book illustrations, trade cards, bills, and medals. The book is readily available online. Tattersall also produced a three-volume catalog of Bewick’s work in 2011, The Complete Illustrative Work of Thomas Bewick with 1,200 black and white illustrations.

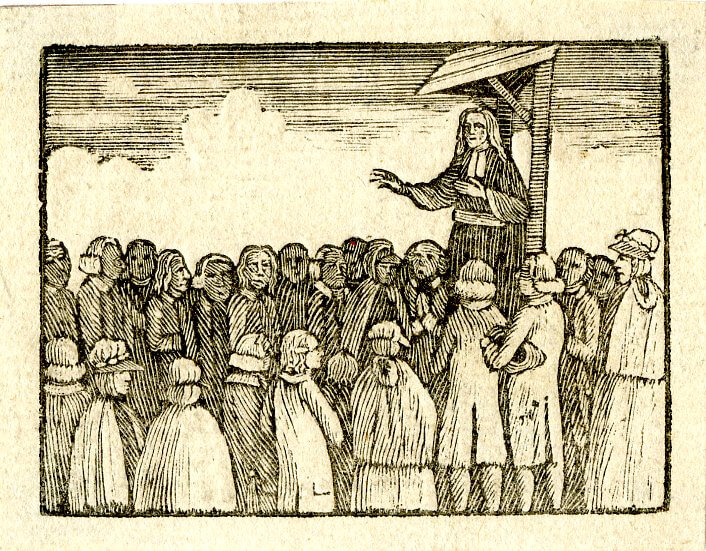

This image struck a chord with my Methodist upbringing. Enjoy the variety of ways the women wear wear their bonnets with their cloaks: on their hoods, under their hoods, and without their hoods. Book illustration from Isaac Watts’ ‘A Choice Collection of Hymns, and Moral Songs’ (Newcastle upon Tyne: 1781, p.11). Trustees of the British Museum. 1882,0311.3923.

Another tender image from Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘Mother Goose’s Melody’ (London: 1781), p.30. Bewick was the father of 3 girls and a son, who followed him into the printing business. His daughters wrote his memoir. Trustees of the British Museum. 1882,0311.3822

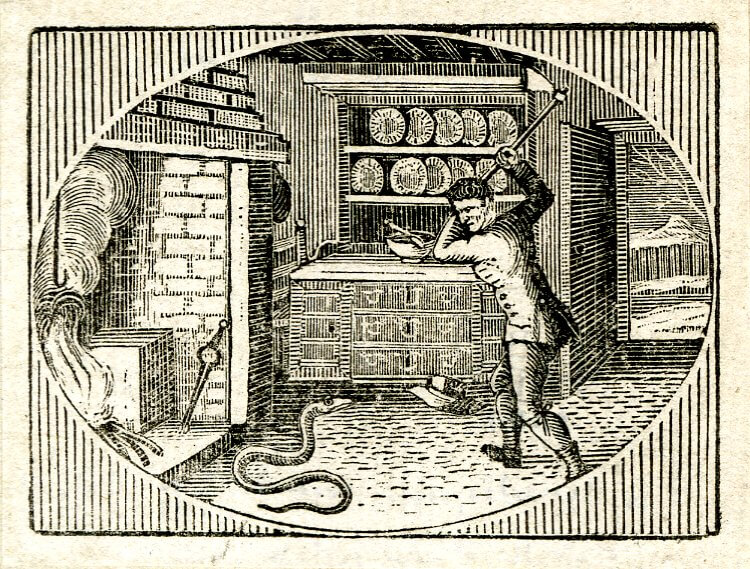

Nice kitchen interior and garters in this illustration from Fable of The Countryman and the Snake from ‘Select Fables’ (Newcastle: 1784). Trustees of the British Museum. 1882,0311.2682

[1] Hugh Dixon. 2010. “Thomas Bewick and the North-Eastern Landscape”, in Northern Landscapes: Representations and Realities of North-East England, editors Thomas Faulkner, Helen Berry, and Jeremy Gregory. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 266