I’ve been a fan of Henry Louis Gates’s programming since he launched African American Lives in 2006. In Gates’s programs, he introduces celebrities to their past through various documents and photographs.

For African-Americans whose family heritage has been obscured by slavery, identifying ancestors prior to Emancipation is difficult, if not impossible. Gates presents his guests with family trees and it is telling that white guests receive scrolls that are much larger and more detailed than those received by African-American guests. I understand how easily white guests like Bill Hader can amass 40 generations worth of ancestors. In my study of enslaved and indentured women in the late 18th century (more on it here), I’ve wrangled with newspapers, indentures, wills, inventories, account books, and personal correspondence. In most cases, a newspaper runaway advertisement is the only piece of documentary evidence that a servant woman existed.

White privilege facilitates discovery of family heritage. I know that even though many of my ancestors were financially poor, their life events of birth, marriage, and death were recorded in legal documents because of they were white. My ancestors wore their heritage as adornment in displays of privilege at DAR and SAR meetings. Online resources quickly reveal that my 8th great-grandmother was tried for witchcraft at Salem and my 11th great-grandfather arrived as a child on the Mayflower.

For the families that emerged from the struggles of American slavery, identifying even one generation before Emancipation is a great triumph. Before 1870, the United States Census recorded those held in bondage by tick marks denoting age and sex, not by name. Documentary evidence often records enslaved persons’ heritage not as life events, but as commercial transactions.

There are current projects to restore the history of enslaved people. At the Virginia Historical Society, the Unknown No Longer project has created a database of the names of African-Americans documented in manuscripts in their collection. I performed an open search on the women in the database and the list of names is staggering. Charity, Moll, and Barbary, held by the Custis family. Phyllis, Betty, and Amey, held by the Bolling family. These are just a few of the names, a few of the lives that can now be studied through this resource. This is a good start to making this type of information in other collections available for study.

Privilege allows me to contribute personally to the work of rediscovering enslaved women and men within the historical record. Below are the names of people enslaved by my ancestors, or ages, where names were not indicated. These references come from wills, inventories, and the 1783 Maryland Assessment for the Revolutionary War. More funding to facilitate access to the information stored in wills, inventories, family papers, and other documents is needed to rebuild heritage obscured by American slavery.

Daniel Scott, d. 1724 Bengies Point, Baltimore County, Maryland (my 9th great-grandfather)

From his inventory:

To 1 Negro man Called Mingoe at 36.0.0

To 1 Negro man Called Sherry at 33.-.-

To 1 Negro wom Called Munsar? At 33.-.-

Gervace (Garvis) Gilbert, d. 1739, St. Georges (Old Spesutia), Baltimore County (now Harford), Maryland (my 8th great-grandfather)

From his inventory:

To 1 old Negro man at 15.0.0

To 1 negro woman at 22 [illegible]

[Illegible] line Negro 6.10.0

Richard Ruff d. 1733, St. Georges (Old Spesutia), Baltimore County (now Harford), Maryland (my 8th great-grandfather)

“Item my Will is that my Son Richard Ruff Shall have one Negro Boy Named Ratliffe he discounting Twenty Pounds out of his part of my Personal Estate.”

Sarah Peverell Ruff (Richard Ruff’s wife) d. 1749, St. Georges (Old Spesutia), Baltimore County (now Harford), Maryland (my 8th great-grandmother)

“Item I give and Bequeath unto my daughter Hannah Bull and unto her in forever my two Negro Slaves Jack and Pheby.”

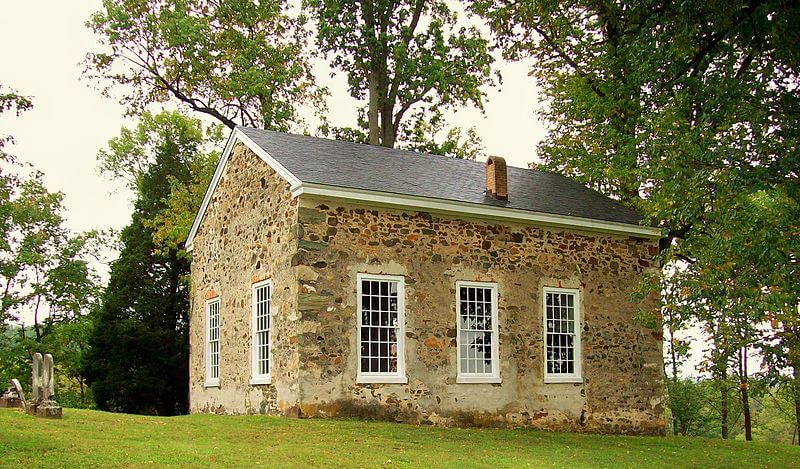

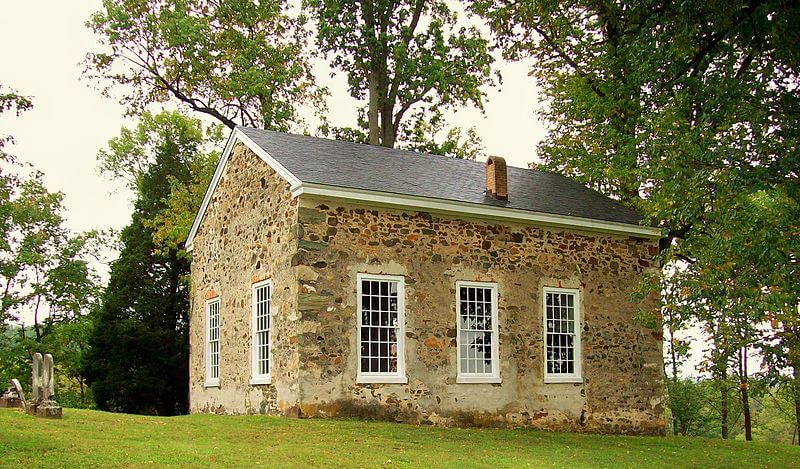

Vestry House, Old Spesutia St. George’s Episcopal Church. The Vestry House dates to 1766. The current church dates to 1850, but the congregation was the oldest in Maryland, founded in 1671. It ended worship services in 2012 due to low attendance. Photo: Maryland Historical Trust.

Henry Ruff, Ruffs Chance (Thomas Run, Harford County) (my 7th great-grandfather)

1783 Maryland Assessment (for funding the Revolutionary War)

1 Child under 8 $6

1 Child 8-14 $25

1 Male 14-45 $70

1 Female 16 to 36 $60

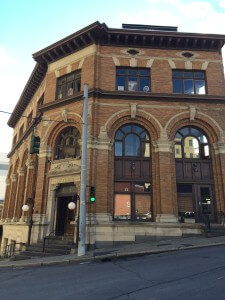

Thomas Run Church. Harford County, Maryland. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

John Botts, Part Eightrip, Susquehanna Hundred (Harford County) (my 5th great grandfather)

1783 Maryland Assessment (for funding the Revolutionary War)

2 Children under 8 $3

1 Child 8-14 $25

Michael Gilbert (Harford County) (my 7th great grandfather)

1783 Maryland Assessment (for funding the Revolutionary War)

2 Children under 8 $35

2 Children 8-14

2 Male 14-45 $140

2 Female 16 to 36 $120

Micah Gilbert (Harford County) (my 8th great grandfather)

1783 Maryland Assessment (for funding the Revolutionary War)

3 Children under age 8 $35

2 Children 8-14

![Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. "Bloc[K]Aded Cars On 23rd St., New York." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 21, 2016.](https://thestillroomblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/nypl.digitalcollections.510d47e1-289c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.001.w.jpg)