Baa. Cool it, already.

Photo: Imaginactory.

John Wily wrote the motivational pamphlet A Treatise on the Propagation of Sheep, the Manufacture of Wool, and the Cultivation and Manufacture of Flax, with Directions for making several Utensils for the Business in Williamsburg, VA, in 1765. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation reprints historic facsimiles of it in their historic area print shop.

Prompting fellow Americans to contribute to the colony’s independence through their own manufacture of textiles, John Wily entreats “For as we have got in Debt by our Indolence and Extravagancy, sure there is no better Method to retrieve ourselves than by our Industry and Frugality. And I must believe, and hope, this small Treatise will forward those Manufactures, as I have given the plainest Directions for the Performance of ever Operation in each of them.”

But what I find interesting is a short passage on in which Wily outlines how to make different types of woolen fabrics and notes a fabric of cotton and woolen to be suitable for house servants:

“If you are scarce of Wool, and have Cotton plenty, you may spin a Warp of Cotton, to run five or five Yards and a Half to the Pound, suitable to a Slay Ell wide; for it will shrink as much in the Width of the Cloth as if it was all Wool, therefore it ought to be wove as wide. The spin Wool to fill in two or two Yard sand a Half to the Pound, and weave it in the Kersey or Serge Way, or any double Woof, and have it milled, and it will appear very well until the Wool wears off, and then the Cotton will show somewhat lighter, unless you died the Cotton of the colour you want the Cloth before it is wove, for the Cotton will not take the Die so easy as the Wool, and that is the Reason it will show lighter when much worn. This Kind of Cloth will wear exceeding well, and makes very good Clothing for Boys or House Servants.” [emphasis mine]

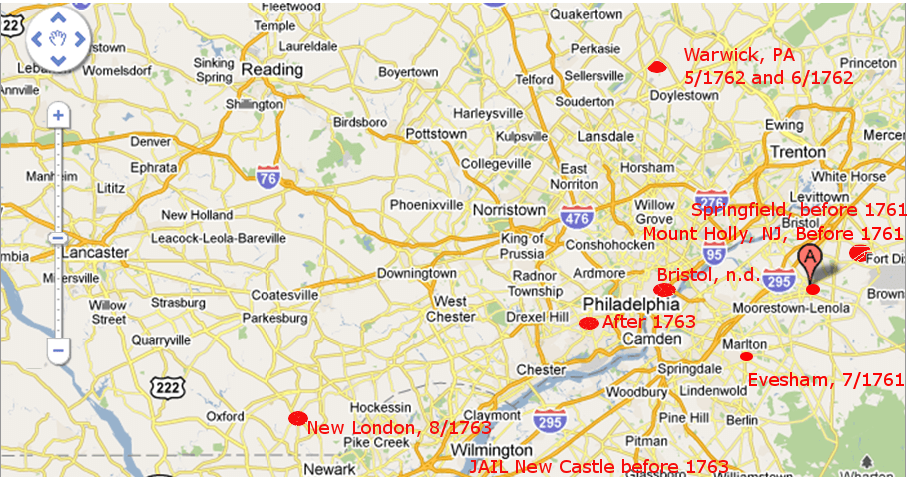

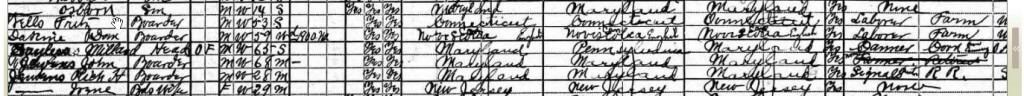

Here’s this type of cloth worn by a runaway servant. You’ll notice in bold, the fabric of her Virginia Cloth petticoat is constructed just as Wily instructs, with a white Warping (the cotton warp) and blue Filling (the woolen weft).

Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon),

Williamsburg, July 16, 1772.

From the Maryland Gazette, 08/09/1787. RL Fifield photo.

COMMITTED to James City Prison, on Saturday the 11th Instanr [sic] (July) a Negro Woman who says her Name is MOLLY, and that she is the Property of the Honourable William Byrd; she is of a yellow Complexion, about forty Years of Age, of the middle Stature, well made, has on an Osnabrug Waiscoat, Coat, Shift, and Petticoat, and a Virginia Yarn Ditto, with white Warping and blue Filling. The Owner is desired to take her away, and pay the necessary Charges. JOHN CONNELLY, Jailer.

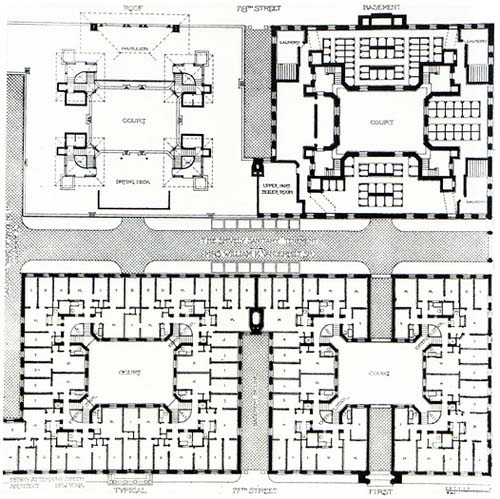

And in considering the long view of woolen production in America, Walker Evans captured the wool industry in decline two hundred years later in this series of photographs for Fortune Magazine, “The Twilight of American Woolen.” (1954)

Walker Evans. Metropolitan Museum of Art 1994.252.17.1-85. From Views of Massachusetts Wool Mills and Surrounding Area, Commissioned by Fortune Magazine for “The Twilight of America.n Woolen”, Published March 1954