Kimono? White makeup? Shamisen music? In New York City?

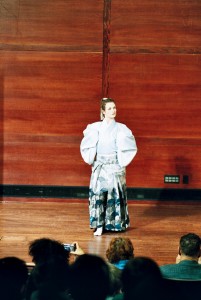

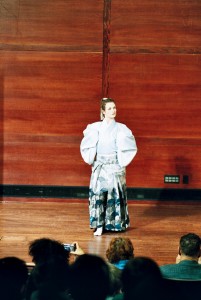

I spent a few years as part of a semi-professional kabuki dance troupe here, as a student. Many westerners might think white makeup when “kabuki” is mentioned, but they might be hard-pressed to describe the dance. It has connections to martial arts, and issues from the kimono-clad dancer’s core, requiring extreme balance and strength. The dancer tells poignant stories by creating a habitat of imagery for goddesses, princes, young women, jesters, and geisha. All parts of the dance are connected: music, movement, and dress.

A performance at Hunter College in 2007. I’m dressed as a young man, including padding to create a male stomach!

I don’t speak Japanese, but I now know a random assortment of Japanese theatre customs, dance terms, stage cosmetics, and visual imagery used on kimono. Saying Ohayu gozaimasu (good morning) to greet each other at all times of the day. Oshiroi, the white makeup worn by stage performers and geisha. Botan, the Japanese word for peony. I can dress myself in kimono and have a basic understanding of the appropriate fabrics, colors, and motifs for different times of the year. At a cherry blossom festival in Flushing Meadows, a Japanese woman expressed surprise when she learned I dressed myself. I love the aesthetic, the look of effortlessness, the far-away glance of the dancer at an end of a phrase, the artistry of kimono textiles.

Nikki Tilroe as The Mime Lady on Today’s Special. Photo: Wikipedia.

When I began dancing, I was the student of Nikki Tilroe, “The Mime Lady” on the children’s television program Today’s Special, the power behind the Snuggle fabric softener bear, and a Muppet puppeteer on Fraggle Rock. I started dancing after a few years of collecting kimono and obi (the large sash worn with kimono). After contacting the Japan Society in Boston looking for a teacher, and a very brief lesson learning ancient court dance called bugaku, I met Nikki-sensei. Tiny and fiery, she indicated that mirrors were not used in Japanese dance classes, but that because we were Western and grew up in a different learning tradition, we would use mirrors. She strew several mirrors around the office space that served as her studio – they looked as if they’d been ripped out of old bars and houses.

At the White Plains Sakura Matsuri in 2005. Note how dancers fold in their thumbs to create elegant-looking hands.

After moving to New York, I joined a group that had been established here by a Japanese-American woman in 1961. The group was in transistion, as their sensei was retiring, leaving the classes in the hands of several advanced natori, or certified dancers who have passed rigorous exams demonstrating their fluency in several dances. Interestingly, few of the women in the group were Japanese American: many of the older students were of Anglo or African American descent, while newcomers were Japanese women living in the US. Teachers of Japanese dance belong to one of many schools in Japan – each has their particular story of origin and particular style. I went headlong into three hour classes on Saturdays. New students would appear, come for a few classes, and then disappear, not ready to make such a commitment. Then I was going on Sundays as well. I was performing at cherry blossom festivals and helping at educational seminars. I met beautiful women who love dance.

After a stage makeup workshop led by Kabuki actors, 2007.

The red makeup used to highlight the corners of the eyes had to be modified for my European features. While I’m not very tall, at 5’6” I towered over most of the other dancers. Kimono are created out of standardized lengths of cloth and most of the width is preserved in the entire garment. In an average-sized kimono, I looked akin to wearing too short pants. I was constantly letting out sleeves to reach down my longer arms. Conversations carried on in Japanese and English. I caught what I could.

Politics are a part of any enterprise – as an American participating in a foreign art form, there were certain obstacles I was not going to be able to overcome. I had excellent moments when I was able to learn one of my favorite dances from the woman who choreographed it, her father a National Living Treasure. But as in many performance-base arts, it became less about dance lessons, and increasingly about the support of the organization and competition. It’s not why I joined. But I still have good friends from that experience, and occasionally I put on kimono for practice. Amazingly, my hands still fold, tuck, and tie everything automatically.

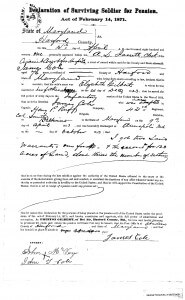

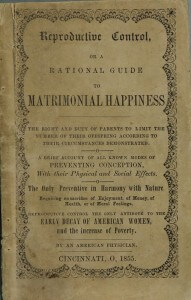

The National Archives, the DAR Library in Washington, the Maryland State Archives, the Pennsylvania Historical Society, the London Metropolitan Archives, Library of Congress, and so forth. I love the click of the microfilm drawer, the smell of old paper, the knowledge of whatever system in that particular archive that will get you the information you seek.

The National Archives, the DAR Library in Washington, the Maryland State Archives, the Pennsylvania Historical Society, the London Metropolitan Archives, Library of Congress, and so forth. I love the click of the microfilm drawer, the smell of old paper, the knowledge of whatever system in that particular archive that will get you the information you seek.