Click here for the first post on the Cole Cemetery relocation.

My mother and I were standing in the Target parking lot in Aberdeen one cool and sunny Saturday morning in April 2010. We weren’t there to shop for hair dye. Instead, representatives of Merritt Properties LLC led us down a steep embankment into the woods next door. Tripping through winter-bare vines, we passed a worn campsite, indicated by charred earth and crushed tin cans. Alongside was a path through the woods, which then widened into a rutted muddy road. An old, weathered telephone pole indicated the farm that used to be located here. Then we saw the mound.

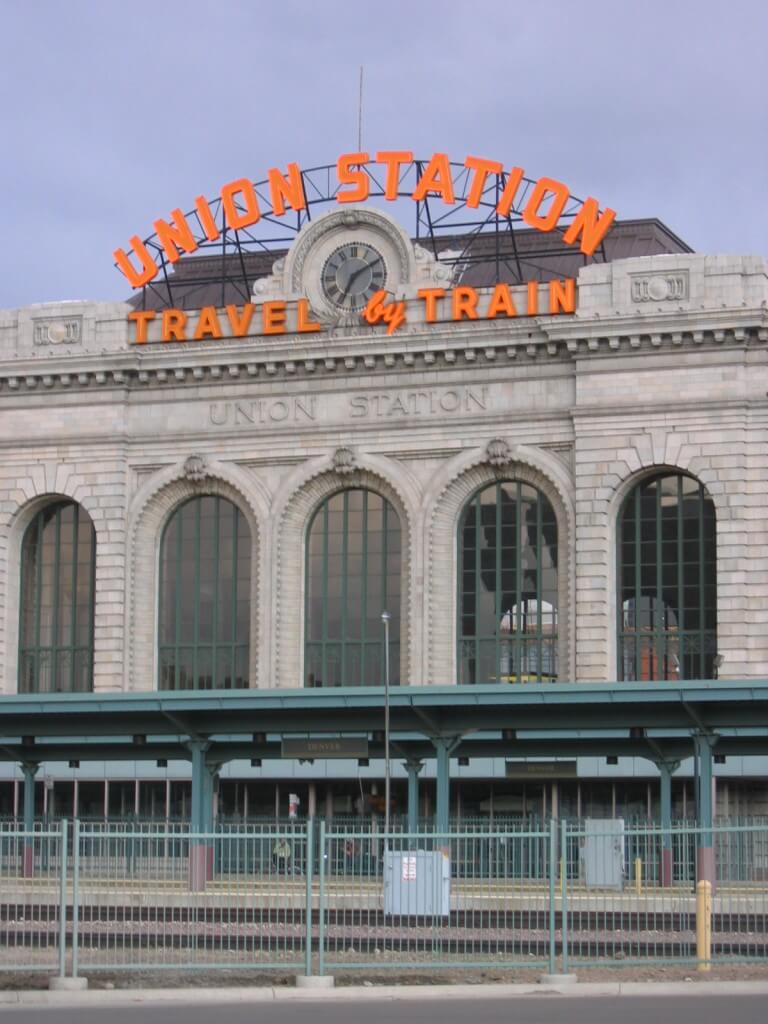

Cole family cemetery mound, Aberdeen, MD, 2010. RL Fifield photo.

Twenty-five feet in the air, up in the trees, people were milling about. Title searches show that our family owned this land from 1757 until 1947. A gravel operation then purchased the property, stripping everything around the cemetery, leaving the mound. ATVs had used the cemetery as a jump, marring the mound with thick ruts. The idea our family had a burial mound was rather thrilling. Climbing up to the top, I could see my great great grandparents’ house from the 1860s sitting nearby, just beyond the edge of the woods.

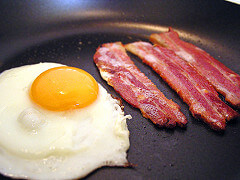

Gibb Archaeological Consulting and Volunteers, Cole Cemetery site, Aberdeen, MD, 2010. RL Fifield photo.

Jim Gibb and his associates were hard at work up on the mound. His presence was the result of rounds of intense telephone calls with the developers, as we worked to understand each other and reach an agreement for an archaeologist to recover the remains, rather than the local funeral home. I was unsure what sort of atmosphere would prevail at the exhumation.

Surprisingly, we found a party. Not only were the archaeologists present, but local historical club members, Aberdeen Proving Ground historians, and local Harford Community College were all helping to recover my family members. It was all hands on deck to help transport the Cole family away from the construction site.

The team works on the grave of Elizabeth Gilbert. RL Fifield photo.

Jim is dry repartee defined, and he teased me for not pitching in. I couldn’t. I stood there the whole day, paralyzed and gaping, waiting to see what else would be unearthed. The one time I tried to help store a textile fragment, I dropped it (and as the joke goes, “I work in a museum”). I thought maybe we’d stay for a couple of hours and leave, but I should have known better.

Nobody likes to disturb people at rest needlessly, but I felt that it was more appropriate to relocate my family down the road to a cemetery where their children and grandchildren were buried, rather than protect their graves in situ as part of an office complex.

The archaeologists studied the ground, looking for changes in the soil to determine how many graves there were and where to dig. Then came the shovels, the trowels, the sticks, and brushes. Wood, textile fragments, glass, metal coffin handles, bone, glass buttons, and even a vulcanized rubber comb that had held my 4th great grandmother’s hair in place all emerged from those pits. Even if the human remains had completely decomposed, as most of the children had done, there were at least rootmats that had grown around where the skulls had been. It was incredible to see how earth, water, and organisms dissolve our remains. I held part of my 4th great grandmother’s femur in my hand; it was as light as pumice.

Coffin hardware decorated with a neoclassical urn. GAC photo.

By the end of the weekend, either the bodies or other materials had been exhumed from the graves of six people: my 4th great grandparents James Cole and Elizabeth Gilbert, another young woman, an eleven year old, a six year old, and an infant. We had them, but we knew little about them, beyond some census data.

Next stop: The National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Click here and here for the next installments.

.jpg)