Who Makes Collections Care Happen?

Easy. Technicians dust artwork. But that’s a little simplistic view of both the work of a valuable, skilled technician, and collections care.

Conservators make collections care happen! They study scientific reasons for deterioration and design and perform treatments to stabilize structure, consolidate painted surfaces, and prepare objects for loan and exhibit. They must care for collections! Conservators are certainly part of caring for collections. Their research can be the reason why behind environmental monitoring, pollutants mitigation, and choosing the right materials for storage. But while lots of conservators do get involved in daily care of collections (ipm, cleaning, etc.) many conservators spend their time treating damage that could have been prevented. I remember this phrase from grad school: conservation is what happens when preservation fails. Many would argue that statement is false, but it points to the different understandings of the words we throw around on a daily basis in our industry.

Okay. How about everybody makes collections care happen? That’s true too – everyone in a museum has a responsibility toward collections care. Eating in a specified area and throwing food trash in a marked, regularly emptied bin limits pests’ food sources. Asking an inquisitive visitor “please don’t touch” in the gallery – and telling them the conservation reasons why – helps extend the message of preservation.

But that’s not exactly what I’m getting at.

RL Fifield taking a light reading.

There is a lot more to collection care than dusting and fixing objects. Collection care covers the range of activities that preserves the intellectual and physical value of collections over time. This includes storeroom management, integrated pest management, working with facilities and construction to develop appropriate environments, selecting appropriate materials for storage, managing projects involving collections to make sure decisions do not affect the stability of the objects, developing emergency protocols, assessing and mitigating risks to the collections, as well as handling paperwork and performing documentation that secures an institution’s title to the work, safeguards our knowledge about a work, and makes that work and its information accessible to researchers and other users. Conservators don’t do all that (thought many private practice conservators advising small institutions may get into these areas). Technicians don’t do all that.

So – who makes collection care happen?

If you go to any doctor, you (let’s hope) receive a set of services that should not vary widely from practitioner to practitioner. From museum to museum, that’s not the case. For a start, museums are all different, house different collections, and have a variation of staffing levels. At the small town historical society, the curator might perform collection care. At the big city art museum, a conservator, collection manager (see my post on What is a Collections Manager?), or preservation officer might oversee and assess preventive collection care activities for the entire museum. At museums in between, a registrar might do these activities. There’s no one-title-fits-all. Collection care practitioners have a variety of titles, an ever-increasing amorphous mush ranging from collection care specialists, collections managers, registrars, collection coordinators, preservation officers, manager for collections, directors of collections. Some have on-the-job training. Many have masters or doctoral degrees. Many have additional training after they graduated. Can you define correctly what any person with one of these titles do, without asking them? From museum to museum, the answer is NO.

(this is hardly a comprehensive list, and does not even try to add in the title of curator, which has long been used/abused/extended/distended and applied to many a museum job – the University of St. Andrews has an Operations and Projects Curator!)

RL Fifield dusts artwork using a hake brush and a Nilfisk HEPA Back Vacuum.

Part of the problem is that collection care isn’t assigned the same importance at all institutions, and don’t worry, I’m not so naive that I’m shocked by that. Concerned conservators who believe we need to do more to counter the damage before it occurs have been working on this since the 1980s. Collections Management and Collection Care training been offered through Museum Studies programs increased through the 1990s as preventive conservation was given more clout. See this article by my professor and former Chair of the Anthropology Department at the National Museum of Natural History, SI which discusses the rise of preventive conservation and collection care training. Another good quote ( another missive from another of my professors, Cathy Hawks, from another source): you can’t treat authenticity. But what happens to the people who go through those Museum Studies programs of varying quality (see my post on that problem here)?

They apply for jobs of varying titles. It might mean they are sitting at a desk all day, or it might require they have hand skills, know what to do with a drill, and can lift 50 lbs. They might report to a Curator, Collections Manager, Conservator, Registrar, or other staff member. They have staggeringly different job descriptions. And if you do get a permanent position (not always a given in these days of contractual arrangements, temporary grant positions, and soft money), what’s next?

The questions I’m asking now are:

1) How do we continue to advocate for collection care within our own institutions? I feel my forward thinking graduate program launched me like a torpedo in the late 1990s, into the realm of traditional museums, with an intent of wreaking preventive conservation on them. But it’s a slow and often disappointing climb to educate colleagues about why your work matters, especially when others seeing you dusting artwork (see my post on Dust). But today, even though I work in a very large institution, I don’t have any mentors doing the work I want. It can make it difficult to understand how I should develop myself as a professional. Many, many conservators, facilities, and other colleagues provide me with handy advice, but their role is very different from mine. Which brings me to…

2) What sort of mid-career training is appropriate for collections care practitioners? Lots of continuing studies training focuses on basic skills, like handling of textiles, or treatments, like protecting dyes/inks on textiles when they are washed by using cyclododecane (that may not be a good example). Neither of these are appropriate for collections managers, who need more training in fundraising, advocacy, and preservation planning. We are having to bust down our own doors, and then write the curriculum. After we get that training and experience…

3) What sort of advancement opportunities should we be looking for, asking for, asking our administrations to develop? I wrote an article which discussed advancement: “Collections Care Specialists – A Legacy at Work at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston” article in Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, August 2005. Unlike Director of Collections (often a curatorial title, but not always in natural history collections), Chief Curator, Chair of Conservation etc., these senior positions have not yet been created for collections care practitioners. For those who want to be more involved in administration, this can lead to burn-out, turnover, and loss of talent to the museum field. Developing advancement opportunities for collection care practitioners requires institutional acceptance of collection care and preventive conservation as systems that work.

To sum up, caring for our collection care practitioners is like an investment in preventive health care: would you rather pay for your art to get a personal trainer, or do you want to pay for a conservator to treat it for heart disease, after the damage is done?

It’s been 7 years since The Silver Spoon, the Italian bible of cooking, was translated into English. I remember hearing a segment on the cookbook on NPR when it arrived on American shores. Somehow I missed opportunities to check it out of the library, and never quite wanted to dedicate the Manhattan real estate to purchasing the tome. I finally hauled home a copy from the New York Society Library (NYSL) last Thursday. See my post on my favorite New York library

It’s been 7 years since The Silver Spoon, the Italian bible of cooking, was translated into English. I remember hearing a segment on the cookbook on NPR when it arrived on American shores. Somehow I missed opportunities to check it out of the library, and never quite wanted to dedicate the Manhattan real estate to purchasing the tome. I finally hauled home a copy from the New York Society Library (NYSL) last Thursday. See my post on my favorite New York library

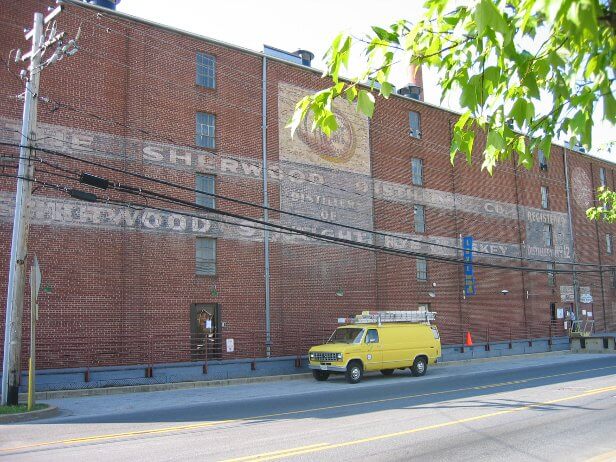

Historical research is like sketching. You begin with a few pieces of data, allowing you to make some bold strokes on a piece of white paper. You identify what sorts of primary resources will improve that image, and it redirects those original lines, lending them further shape. You may find your original lines terrible and embarrassing. The exercise is not to simply connect the dots, as there is still a lot of interpretation required on the artist’s/historian’s part to bring the clearer picture into view. Between the dots are infinite shades of gray, while each bit of data requires contemplation, acceptance, and often, discomfort on the part of the historian.

Historical research is like sketching. You begin with a few pieces of data, allowing you to make some bold strokes on a piece of white paper. You identify what sorts of primary resources will improve that image, and it redirects those original lines, lending them further shape. You may find your original lines terrible and embarrassing. The exercise is not to simply connect the dots, as there is still a lot of interpretation required on the artist’s/historian’s part to bring the clearer picture into view. Between the dots are infinite shades of gray, while each bit of data requires contemplation, acceptance, and often, discomfort on the part of the historian.